Holding the Invisible: a Personal and Historical Reflection on Mourning Jewelry

- Feb 11

- 2 min read

Memento mori.

Ex-votos.

Talismans and amulets.

Reliquaries.

These kinds of jewelry and objects have always fascinated me. They’re designed to hold something—a reminder, a prayer, a meaning, a relic—and something about that has always stirred me. I could never quite name why, until I experienced my own encounter with intense, traumatic grief.

Suddenly, I needed a place (a vessel, a container, an object) to represent and hold my feelings. When people talk about needing to feel their feelings, I found I needed to make something to feel them with.

The words memento mori, ex-voto, amulet, and reliquary entered my world as a language as I used them to lean into ways to design, create, and explore what mourning jewelry could be.

Historically, mourning jewelry has expressed connection to the deceased. The Victorian era is perhaps the most recognized for it, especially for its experimentation with materials: ashes, hair, wood, enamel, steel, jet, pearls, and painted eyes, each chosen to embody memory and remembrance.

Before that came amulets and memento mori adornments. Amulets have existed for millennia as means of protection, invitation, and warding. Much of Ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman jewelry was talismanic by nature, from the choice of gemstones to the imagery itself, every element signaled a relationship with omen and intention.

Memento mori, Latin for “remember death,” became especially resonant during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, not only in jewelry, but in still life paintings, too. Both memento mori and amuletic jewelry invoke a relationship with the unseen: a mute dialogue with ancestors or guiding spirits, inviting their protection, direction, and wisdom.

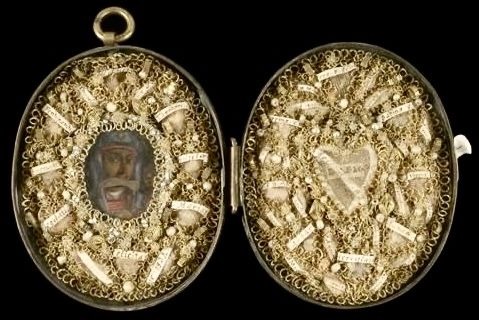

Finally, reliquary objects and jewelry. These are most associated with preserving bones, hair, cloth, tears, crumbs, dirt, wood, anything once touched by martyrs or saints. Perhaps that’s why the Victorian era did not flinch when experimenting with alternative materials; they were following a long tradition of holding presence through remnants.

These sacred fragments are often laid on velvet pillows and adorned with precious metals and gemstones, now resting behind glass on altars or in private rooms. I’m especially drawn to the small handwritten notes placed beside them, curious identifications that tell who the relic belonged to, and what it once was.

On my new path, I am feeling very drawn to these traditions as a way to discover how an object can carry emotion, memory, and devotion all at once. To me, each piece becomes both offering and conversation. A reminder that what’s gone still speaks to us.

Thanks so much for reading.

Take care for now,

Caitlin

Comments